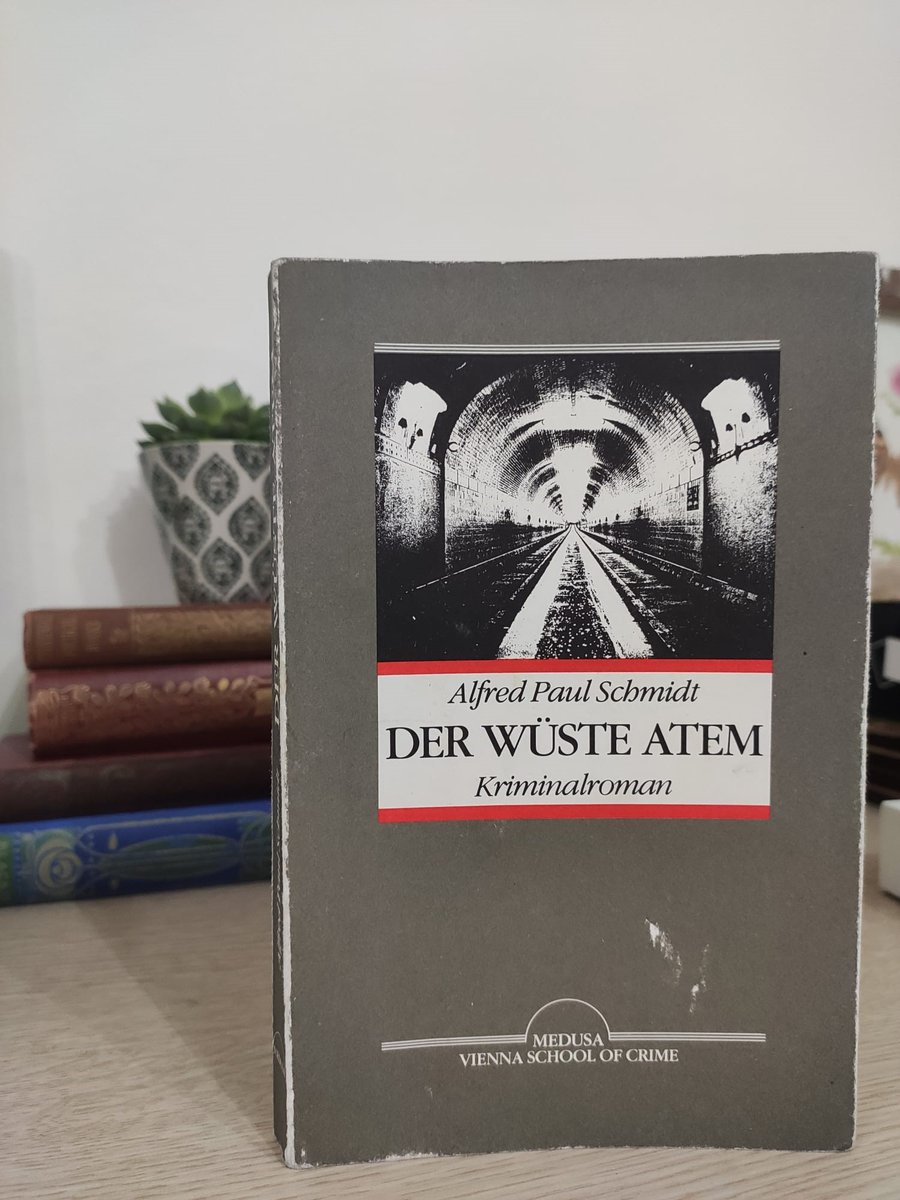

An unsettling story captured through the fascinating perspective of a psychologically complex main character. Der Wüste Atem, or the desolate breath, explores the theme of criminality through a less conventional and more psychological perspective, by diving into the mind of an everyday criminal instead of being content with a mere description of event. The protagonist, Bubi Hassler, finds himself to despise his current life situation, and believes that he must act in an attempt to free himself from his burdens. He feels trapped, wronged by everyone that surrounds him, and without control over his own life. The narrative reaches its climax when Bubi decides to act upon his supposed misery. While he believes that he managed to free himself, the reader realises that the more the story continues, the more Bubi’s decisions and actions are tied to that event; this event dictates his course of life, and eventually the end.

What particularly drew my interest was the stark contrast between the monstrosity of Bubi’s actions with his rationale: every act he commits is justified, and if the ‘Bilanz ist positiv’ (p. 112), even better. All secondary characters are described as burdens that Bubi tolerates; his condescending character makes one believe that he has a god complex, destined for better things. This rather convoluted psychological profile is however so well conveyed by Alfred Paul Schmidt, that even German learners, such as myself, are able to understand its nuances. What I also found interesting was the use of Austrian words, that I was initially not familiar with, but allowed me to further immerge myself in the context of the narrative. The initial sympathy felt for the protagonist slowly evolves into a sense of apathy and appalment.

Overall, the story of Bubi Hassler remains an interesting depiction and exploration of a potential narcissistic sociopath, who does not take into account any repercussions that his actions might have on others. In addition, the fact that the narrative takes the point of view of the criminal instead that of the victim brings a different perspective to crime: rather than approaching it from a judgmental perspective of a detective that aims to fight the evil, the reader is submerged in the inner thoughts, reasons, logic of a criminal, who does not necessarily consider himself a criminal.

Finally, the ending of the novel was considerably abrupt, leaving the reader satisfied by the outcome. However, in light of its shortness, one can conclude that the importance of this novel is not found at the end; Alfred Paul Schmidt wanted perhaps to give the emphasis on the themes of psychology and character description, rather than stall his narrative on the overall goodness or evilness of the crimes committed. While this plot is not the obvious pick when one thinks of criminal novels, I thoroughly enjoyed reading it and highly recommend it to whoever enjoys such psychology-focused novels. I would also highly recommend it to German learners, especially those interested in the Austrian German, as Schmidt wrote an advanced yet accessible novel, which allows German learners to understand the plot while improving their reading comprehension; and Austrian German enthusiasts to add Austrian words to their lexikon.

Anna Anagnostopoulou

This review was written for the ACF London's EXPLORE OUR LIBRARY initiative.